It’s been a while since I wrote anything for this newsletter. I’ve come close a few times, but always reconsidered. I’ve been busy, but mostly I haven’t felt especially engaged. Every time I sit down to write I get this vague, unfocused feeling and am unable to crank out anything longer than a few sentences.

Maybe it’s a curse. For ten years my father stared at the photos and letters of this man, his great-grandfather William Herring. William Herring was, among other things, the assemblyman in New York who annexed the better part of the Bronx from Westchester County and codified Decoration Day on May 30th. He also was the first attorney general of the Arizona Territory as well as the first chancellor of the University of Arizona. He fathered four children and famously refused to raise a flag over his Tucson house until Arizona achieved statehood. He even defended Wyatt Earp on a murder charge, Earp having been accused of shooting Frank Stillwell.

My father was trying to write something about this man and his family, my dad’s family. My family. And as much as he researched, he wasn’t ever able to write much at all. So yeah, maybe it’s a curse.

After writing the post on Memorial Day this past May, I hit on the idea that maybe it was me, not my father, who was charged with writing the family history. Not history, though. Just a story built on it. Maybe a novel. I was thinking East of Eden, or maybe Angle of Repose. If you’re gonna plan, set the bar high.

But then I reconsidered. A novel was too daunting, and I already have four in progress (or is it five now?) Instead, I could try a cycle of short stories that all revolved around the various characters: how my grandmother, newly graduated from Wellesley with a two-year certificate in physical education and about to embark on a teaching career in Tallahassee, met my grandfather on a golf course and (over time) fell in love with this uneducated southern man. How my grandfather, ashamed of his lack of education, took the Harvard five-foot-shelf of books with him on an epic trip to Tucson in a model T after my grandmother went home to grieve for her father.

About how my own father had gone to the Art Center School in Pasadena because his aunt and uncle who founded it had offered him free summer art school, and how two summers with his sadistic uncle utterly killed whatever art spirit he possessed.

Other stories. Young Howard Herring, whose terrible teeth brought him to an inexperienced dentist who injected him with so much cocaine that he fell to the floor in convulsions and died. How the Bisbee Mob broke John Heath out of jail and strung him up in front of the Herring house in Tombstone. Or my own youth running through alleys dressed as a WW2 infantryman. So many stories.

There was a photograph of William Herring that stood framed in my grandmother’s library along the same shelf that held black-and-white portraits of most of my family. They all seemed to be looking upward or outward.

The only one staring straight at me was my dad, in his high school senior picture.

I stare now at the photo of Colonel Herring. I’ve only seen two. They seem to be from the same time, around 1898. He is bald, glabrous, portly, with pale eyes that seem to jut from his face. He has a cleft chin above his wattle, and a wild west mustache. In both photos he wears a low collar and a black bow tie. I can almost hear my grandmother’s voice saying “Granddaddy weighed 300 pounds and we were so proud of him!”

I remember reading in the musty newspaper about Colonel Herring driving out from his house on Main Avenue to the newly-constructed University of Arizona which then consisted of a single building surrounded by a low stone fence and a large, incongruous wrought iron gate.

When Colonel Herring and his party arrived, this gate was chained shut. With great flamboyance, he sent his coachman back to the house of an axe. He then smashed open the lock, declaring to the accompanying newsmen that “the Gates of Knowledge shall never be closed!”

Or so went the story.

He was, to me, a ghost. An old man.

I’d never thought of him otherwise, except perhaps as a colorful character. I’d never seen a photo of him as a young man, knew nothing of his past except in anecdote or lore.

My dad knew a great deal more, but my dad is dead and I have no access to any of the family papers. Thirty-three years ago I was able to read the Home Journal that documented the daily life of the Herring family from their New York days to the mining camps of the Arizona Territory and then to Tombstone up until Howard’s death, when they lost interest in the chronicle.

So now like my father before me I stare at the ghostly photo of this man whom I never knew. I feel compelled to tell something of his story, but like my father I don’t feel adequate to the task.

And like my father I want to start with the pencil.

When my dad was cleaning out the basement he came upon what looked like a blackened nail-set, albeit a very fancy one. He quickly realized it was a sterling silver mechanical pencil from Tiffany & Co, set with a sapphire and engraved To WH from SP. It was the clue that set him on the trail of why exactly his great-grandfather had left such a promising career in the New York Assembly to compulsively seek his fortune out west at the ripe old age of 48.

Based on my recollection of what my dad told me he’d found, I began to write a story about it. Maybe it’s the first of this cycle I mentioned earlier and it will appear in a finished form elsewhere, or maybe this is as close to finished and/or published it will ever be. You be the judge. This is a draft, so buckle up for some rough prose.

THE COLONEL TRAVELS WEST

From behind his desk Bill stares at the man in the doorway, the tight-buttoned suit and prizefighter's nose out of place in this primly paneled office. He also hasn't removed his hat, a bowler crimped high on his small head.

“Got something for you, Colonel,” says the man, his voice tinged with the cobblestone timbre of Five Points. “A letter that got misplaced.”

“You are from the Hall,” replies Bill.

"Come on, Colonel," the man replies. "You know the Hall is on the outs. Boss Tweed is long gone, and Wickham ain't taking a second term, just like you crusaders wanted. Moral reform and all. Speaking of morals.” He reaches into his breast pocket and tugs out an envelope. “Addressed to you. Marked personal and confidential. I guess whoever opened it could't read too good."

They’d been lying side by side in the hotel bed at Saratoga Springs.

I wasn't sure you were still interested, she'd said.

I was always interested. You knew I was.

Well, you never wrote me back.

Wrote you back?

After the Christmas party I sent you a letter. It was pretty explicit.

Explicit how?

Oh, you know. Passionate. But you never responded, so I wondered if I'd misjudged things.

I never got a letter from you.

Are you sure?

To what address did you send it? Not my home, surely.

I would never! I sent it to the office.

The letter, she’d said, was addressed to him, marked personal and confidential. Only he would open it. Susan naively believed the mails were sacrosanct.

But Bill's office was served by the same Tammany-controlled post office that had protected Boss Tweed for decades with postmen who never scrupled to open anything that interested them, especially letters to the Hall's enemies––of which Bill was one, everlasting. Ever since his term in the legislature, Bill suspected that agents of the Hall might intercept and read his mail, so he was careful that to keep written correspondence to a minimum. Negotiations were done face-to-face whenever possible, preferably outdoors. Too many men in New York had unwittingly provided Tammany with damaging information by trusting the mails. The mails were never safe for enemies of the Hall.

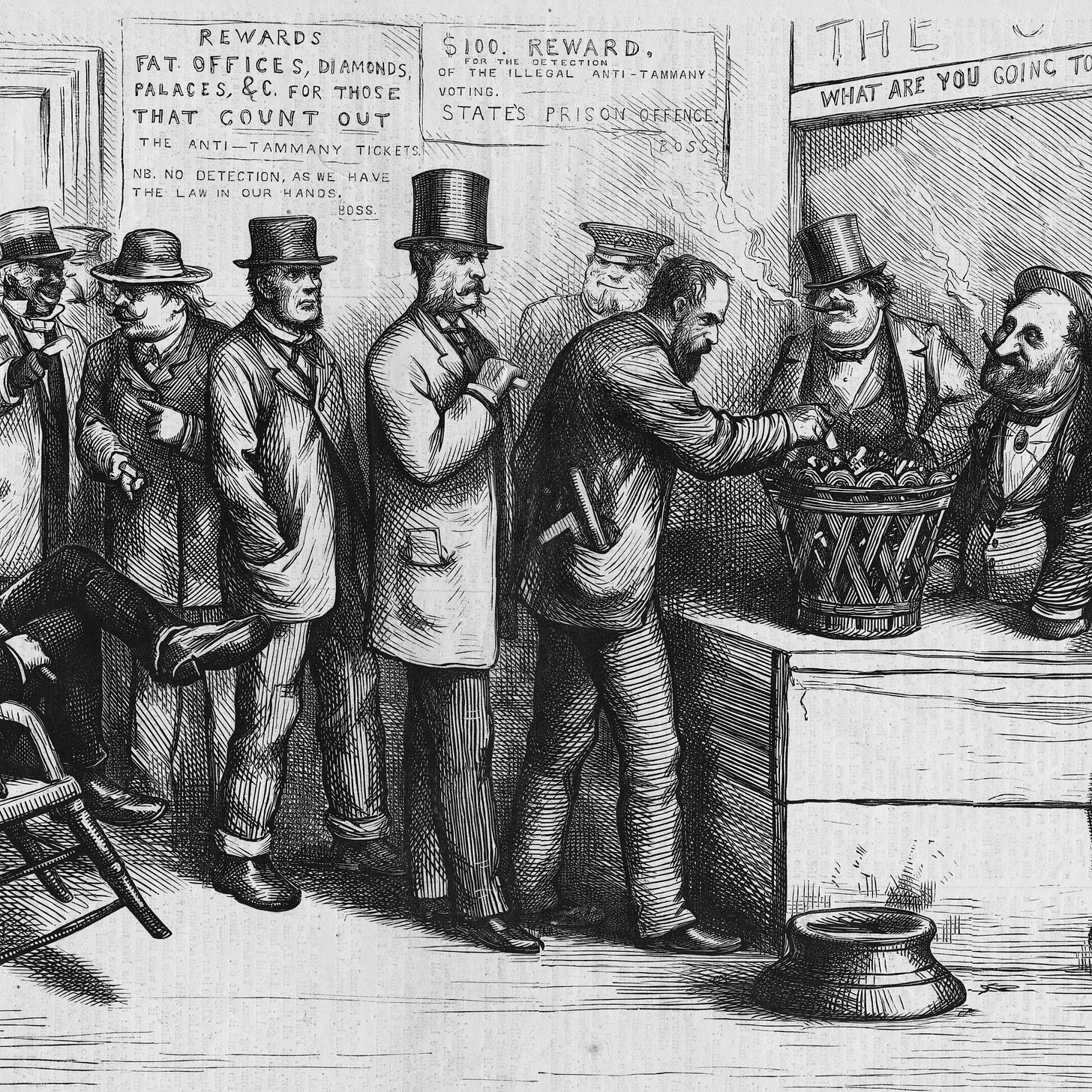

And Bill was a sworn enemy, a Lincoln Republican who strongly believed that government had no reason to fool with business, and vice versa. Tammany Hall was the antithesis of this––snakes’ nests of ward heelers, municipal judges and crooked cops, of yes-men in the assembly and all the local boards, everything and everyone dedicated to staying in power so they could keep funneling public money into a few private hands. This sick corruption outraged Bill to the point that he campaigned for the office of New York Assemblyman on the single plank of prying loose the Tammany grip on city government. W.R. Hearst backed him and several other reform candidates with numerous endorsements in his New York Journal, so even in a Democratic district Bill was elected by more than six hundred votes, the first Republican in three decades.

With thundering oratory, Bill introduced a flurry of reform-centered bills, the centerpiece being legislation that annexed a large part of Westchester County to the Borough of the Bronx. It was presented as municipal improvement, but the main purpose was to weaken the Manhattan-based Tammany majority.

While the legislature was debating the act, Bill received several anonymous notes threatening violence and worse. He took them seriously enough to venture down to a Five Points hardware store where he purchased the .442 Bulldog revolver that he'd carried in his pocket ever since. The law passed and the Bronx more than doubled in size. Wags in the legislature presented Bill with a silver loving cup engraved with Orator of the House, and the governor bestowed upon William Herring the Order of Colonel of New York.

After the ceremony, the governor took him aside and asked him not to seek a second term. "You attract too much ire with your speeches, Bill," he'd said as they sat in the overstuffed leather chairs of the Columbia Club. "But you’ll make a hell of a great DA unless there’s something else you’d rather do.”

“Tell you the truth, Governor, I was thinking about getting back into teaching.”

“That’d be a waste of your talents, Bill. How about I make you the assistant DA and also temporary superintendent of schools? I’d consider it a favor.”

Bill smiled. “Well, since you put it that way.”

#

After Susan told him about the letter, Bill figured it was only a matter of time before the Hall found a way to use it against him. The smart thing would have been to break off the affair, act as if it had never happened. But he passion he felt for this beautiful young woman who was not his wife, was nothing like his wife, was something he had never experienced. He just could stop seeing her. Cynically too, he knew the Hall would come for him whether or not he ended it , so with a recklessness more characteristic of his elder brother Joe than himself, he kept it up.

They were discreet, of course, traveling upstate on separate trains and posing as a married couple at the various inns and hotels. And they had gotten away with it for all these months. Nobody suspected anything as far as he knew. Not his wife or his daughters, nobody on the board, none of the governor’s staff.

But the constant secrecy weighed on him, the dual life of duplicity. He tried to keep from falling wholly in love with Susan, but he could not. The more he loved her, the deeper the deception. He and Mary had never been properly in love when they married. It had been more of a business arrangement, a way for a middle class New Jersey boy to warrant a Park Avenue townhouse and a summer mansion on Long Island Sound. Mary was sensible and practical, but she was also dull and stolid, a poor companion with a sad penchant for moralizing. After Bertha was born they slept in separate bedrooms and never so much as held hands. And yet she was his wife. They had taken a vow together, and he believed vows were sacred. At least he once had.

"What do your bosses want me to do?” Bill asks the man now.

"I'm sure I wouldn't know, Colonel. I'm just the messenger."

Bill stares hard as if trying to break his face with the power of his gaze. "Hazard a guess."

The man grins, showing cracked teeth. "Maybe they want you to have a sudden health problem that forces you to resign. Maybe these health reasons would force you to leave the state. But like I say, I'm just the messenger." He places the envelope on the desk. "I'll leave this here."

#

When Susan first came into the office to interview for the secretary position, her attractiveness and self-assurance were remarkable for such a young woman. She’d presented her degree from Wellesley and packet of reference letters.

During their conversation, he’d found himself glancing at the wisps of stray black hair escaping her hat. At some point he realized was breathing hard, though he soon put this out of his mind and got on with the their interview.

After he'd hired her–––there was no question, given her sterling credentials and letters of recommendation––he found himself making excuses to speak to her throughout the day, assigning her tasks that required close coordination with him, personally. There was no shortage of tasks––the department was a shambles, its many districts more or less incorporated but largely unmanaged. There were few standards and no curriculum, the quality of education wholly dependent on the teachers at hand.

Susan turned out to be far more than the secretary his modest budget allowed––her innate ability to impose a logical structure on chaos proved invaluable. Together they drafted a code of ethics for all teachers and a basic curriculum for each grade. Susan helped him requisition a budget extension that afforded safety inspections for the facilities, standardized exams for teachers, and even some extra funds for kitchens in the poorer neighborhoods. They worked together six days a week, sometimes twelve or thirteen hours a day. Yet the time passed quickly. Susan was inexorably cheerful, considerate, and kind, but more than that; she was witty, and humor was a virtue Bill prized above all others.

One morning as he sat at the oak table in their conference room waiting for Susan to come into work, it occurred to him that he had fallen in love with her. This revelation struck him as preposterous, and also sad. He was a married man more than twenty years her senior. He was going bald and, though still tall, he had been growing stout with the lack of exercise. An old fool blindsided by romantic notions.

Yet he also had the growing suspicion that the attraction was mutual, and that were he to be so bold as to make advances, they might be welcome. His chance came after the governor’s annual holiday party. Bill’s wife Mary was unable to attend, so Susan accompanied him. They cut a charming figure, he in white tie and tails and she gowned in vivid green with red trim. They dined and danced, and in the coach ride home they kissed. Bill found to his delight that she was more than receptive.

During the next three weeks of holiday with his family he thought of her constantly. He remembered the fine taut feeling of her body beneath the wool of her coat, the fresh firmness of her face as he kissed her. His eldest daughter Sarah accused him of wool-gathering more than once, darting curious looks at him.

One of Bill’s great pleasures was the Sunday dinner conversation with his family. The table laid, the family would file in and sit in their accustomed places. With great ceremony Bill would take out his Sunday Times and read selected subjects until the family agreed on the week’s topic.

While they ate, a lively back-and-forth would commence. Sometimes Bill would take part in the debates, but mostly he enjoyed sitting as judge and jury while his children argued because he could lose himself in watching them.

Sarah was a fierce debater who employed a tactic of seeming to agree with certain points. She would sidle alongside her interlocutor, then suddenly derail their argument with a deft deployment of logic. Sarah’s reasoning was flawless, her memory awesome, and she possessed the hunter’s instinct of the born prosecutor. Bill often thought that was too bad she wasn't born a male, since she might have climbed all the way to the presidency.

Howard, his youngest and the only boy, had the best disposition of any of the children, sweet and cheerful and abundantly kind. Howard wanted to study law when he graduated high school, but Bill wondered how good he would be at it. Howard had the dreamy temperament of an artist, an unfortunate attribute for a lawyer.

The middle girls, Etta and Bertha, were polar opposites. Etta was like Sarah, but even more willful. She lacked Sarah's technical precision of argument, preferring to batter her opponents with everything from conjecture to ad hominem attacks until they gave up. Nobody could match Etta for tenacity, so after a while nobody tried. Bertha was even sweeter than Howard and rarely took part in the family debates except to occasionally throw her support behind whomever she thought was losing.

His wife Mary never took part in any of the debates. She would sit at her in end of the table in quiet contemplation, occasionally coughing into napkin if the tone of the conversations started to drift toward incivility. Mary was an old-stock Connecticut Yankee with unimpeachable moral rectitude, considering civility at table to be a cardinal virtue. Dinner was the one place Bill appreciated her gravity, since it allowed him to show his playful side. The rest of the time he found it tiresome, dull, even oppressive.

The worst was that since meeting Susan, Sunday dinner had been spoiled for him. The delight of listening to his children debate one another was suffused with a longing for Susan, for what she would think and what she would say. He would stare across the table at Mary and wish that it was Susan sitting there. She would revel in the conversation, likely matching Sarah and Etta in wit and willpower, while still being as kind as Howard and Bertha. In his mind, Susan would have been the perfect foil, the perfect binding agent.

But he took pains to ensure his two worlds would never touch. He was careful at Sunday dinner to never share any of the many things Susan and he talked about, even in a general way. He didn’t trust himself to keep the secret, not did he want to objectively to consider what they were doing.

#

The Hall man in his tight coat and ill-fitting bowler sets the personal and confidential letter on his desk. He touches his hat and leaves.

Bill feels a guilty relief as he stares at the opened envelope. He picks it up and studies the address written in Susan’s elegant script. He feels a flare of anger. She could have just handed it to him in person. How could she have been so naive? Without reading it, he puts into the top drawer where he keeps his correspondence. He pushes back his chair and is reaching for his coat when the idea hits him. He opens the drawer again, pushing Susan’s envelope aside.

He takes out the letter from his brother Joe. Maybe that’s the answer.

Silver City, NM Trty April 3, 1879

Dear Bill,

Greetings from the frontier. Ha ha, not really. Silver City is downright civilized compared to where I just been, which is the Dragoon Mountains in the Arizona Territory. You may have heard to the big strikes in what they are now calling Tombstone (an unlucky name if ever I heard one, but no poor effect thus far). It’s only been going for a few months and they are already pulling out millions in silver.

That’s why I am writing to you. I staked a claim with a fellow I met down here who knows his minerals, George Eddleman. George thinks our claim is sitting on a mountain of copper. I know you’re probably saying to yourself that copper isn’t gold or even silver, but you’d be mistaken. The best piping for steam engines and houses is made of copper, and they’re using the wire for telegraphs now. In the next century, I foresee copper being mighty important, and the man who owns the mine will be sitting pretty.

I hired a lawyer out in San Francisco, a man named DeWitt Bisbee, to see about forming a corporation so we can get capital to start our operations, but as you know I don’t have your head for business or the law. I’d really appreciate your advice and counsel on this, and am prepared to introduce you as a partner. With your swell connections, getting financing should be a cinch.

If you want in on this, we have to hurry. Our claim abuts another called the Rucker that was staked last year by a couple of army scouts, but so far they haven’t done much with it, but claim-jumping got so bad in Tombstone they had to bring in a marshal AND a sheriff to calm things down. It’s not to that point here yet because it’s copper instead of silver, but you know how men can be.

The Southern Pacific line will likely be done by the time you get this, so I suggest taking the train from New York to San Francisco and coming on to Tucson from there. From Tucson you can catch a stage that runs weekly to Tombstone. There are a few different outfits you can use, but I recommend Jack Kinnear. You can find his office in the livery stable at Meyer and Pennington streets. Both Jack and his driver Sam know me, so if you tell them you’re my brother they can get you to our camp.

I close in hopes that you start setting things in motion as soon as ever may be. We need your help down here, and it will be more than worth your while.

Fondly,

Your brother Joe Herring