Here’s a piece of a story for you, one of those I started before setting it aside. I have notes outlining how the central characters wander the country in the opening decade of the 20th century. Hopefully I will get back to it once our move to Washington is done.

Thanks for reading!

THE MANTLE OF CHARITY

Although education may have done much to ameliorate their condition, but few can rise out of a condition of dependence. They may become self-supporting, with friendly guardianship, but not self-controlling.

–F.M. Powell, The Care and Training of Feeble-Minded Children

The man leans against the side of the tractor. It’s green as a Junebug, with bright yellow wheels tall as the man’s shoulder. He taps at the painted illustration on the side of the machine, a grinning farm kid beneath the scrolling letters WATERLOO BOY. "Looks like you, don't it?"

Cholly walks over and studies the picture. "You reckon?"

"Sure I do," says the young man. "And I bet you could drive it, too."

"You reckon?" says Cholly again.

I can see he is excited despite himself, trying not to show it.

"Nothing to it," the young man grins. "Once you get her started."

He begins to show Cholly how to prime the motor with gasoline. Chubb, the farm superintendent, interrupts.

"I think that's enough for today." he says, hands on hips. "You don't want to rile these boys, Mister. They're here for a reason."

The young man shrugs, pulls a rag from his pocket and wipes his hands. "I didn't know he was one of the inmates."

"They are residents, not inmates. And they are here for a reason. Remember, appearances can be deceiving." Chubb takes Cholly by his arm. "Come along, Charles."

I can see Cholly stiffen. He probably wants to hit him, but we all know how that would wind up.

We strive to develop the best in them, and to make them feel that they can do something well and be of some use. Few of our children have the mentality to apply more advanced knowledge in their daily lives.

Cholly is not a moron. Nor is he a feeb, a spastic, or a chink-eye. He doesn't have fits. He speaks clearly. He can read and write, though he pretends otherwise. You meet him on the street, he'd strike you as a normal young fellow, good for a clerk or a farmhand.

But like me, Cholly is a moral defective. That means that according to the state, there is something wrong that makes it impossible for us to fit with society, something monstrous and inhuman lurking beneath our normal appearances.

Out of a population of fourteen hundred at the Institution, fifty or so are in this class. The youngest is five, the eldest in his thirties. Most of us were brought here by a relative. Parents, grandparents, aunts or uncles. Some had it held over them for years prior, an all-purpose threat that one day was carried out. For others it came as a surprise, a train trip for two to Glenwood with one return ticket.

Cholly says he was eight when his mama brought him here. I can't do a thing with him, was all she'd said. Dr. Mugridge was in Des Moines that week, so an assistant superintendent performed the examination. He spent ten minutes asking Cholly's mama questions, then categorized Cholly as a medium-grade imbecile, which is the exact same class to which they assigned me. As with us all, he was taken to the softening room for five weeks of silent solitary confinement. His mother left, apparently satisfied.

We do differ in that I am one of the few sent here by the law, the sole survivor of the house fire which they suspected, but couldn't prove, I set. And in fact I did set it, for good reasons, namely that I was tired of my stepfather coming into my bed, tired of my mother's blind eye.

One January night I'd had enough. When Jackson came I'd tried to fight back, but he pinned my wrists and give me a couple hard hits in the face with his fists before he flipped me over. I could smell the whiskey on him as he pushed me into my bed.

When he was finished with me he went back to the bedroom he shared with my mother. I could hear his snoring through the walls, loud as a hog in a gate.

I lay there in my pain and sorrow for a long time, unable to sleep. After a while I went down to the kitchen and fetched up the kerosene tin. I took my blanket and piled it against their door, then poured on the kerosene. From there I walked backward, dripping the can as I went down the stairs and into the kitchen.

I struck a blue-tip match and dropped it on the puddle, the blue flame licking away like a bird flying along a river, straight up the staircase and onto the second floor. I pulled on my boots and overcoat, then went out to the privy.

It was a cold night, the wind moaning over the fields and kicking up dry wisps of snow. I could see a yellow flicker through the chinks of the outhouse door as the house went up like a bonfire. I stood shivering while I watched the house burn down, my frontside roasting while my backside froze. The volunteer fire company arrived just before dawn, but by then there was nothing to save.

The town marshal questioned me closely, but I pretended to be struck dumb by the tragedy and said not a word.

"The boy's touched," he said, and a week later the courts shared this conclusion and so remanded me to the custody of the State Institution For Feebleminded Children. The train trip took a full day, a deputy marshal never leaving my side. I was eleven years old.

These older children are, as a rule, happy and contented, and fit in their niche in institutional life far better than they would in the complicated outside world. They receive direction and are under control. On the outside most of these essentials are lacking, and in many instances it seems to be courting disaster to disturb their life in the institution.

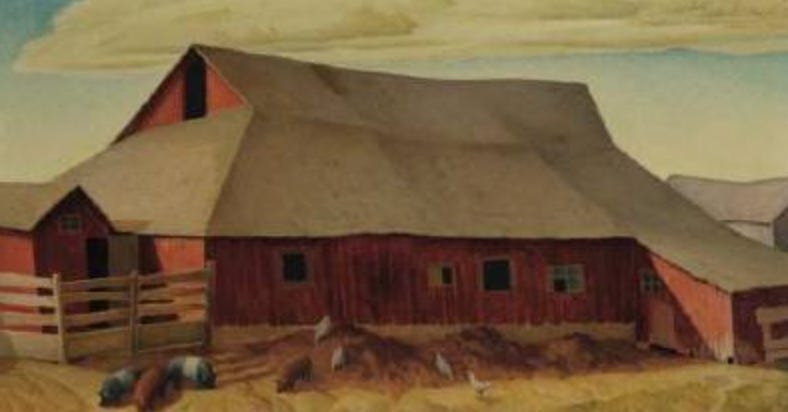

The State Institution for Feeble Minded Children is the pride of Mills County, a Kirkbride design of pale granite with an ornate central structure and long wings stretching out either side like arms held wide for an embrace. There outbuildings, barns, workshops, and separate quarters for the staff. All of this surrounded by farmland, gardens and fields.

There are no fences or walls because that would make it seem like a prison, and the staff takes great pains to disprove that impression, always striving to show the community how useful and upright we are, we hard workers who will one day be a credit to society.

One favorite way is the Open House Wednesday where anyone can stop in and take a guided tour. The visitors arrive at the circular driveway and walk up wide granite steps through the tall double doors into a marble lobby with high windows and a brass-bound staircase that coils to the upper floors. They can tour the offices with their broad oak desks and green glass lamps. They are guided into the two public hallways that span off the main building where they can peer through the door-glass at the crafts room, the gymnasium, the library, and the dining hall.

They also can see the two residence rooms on display with bedspreads and throw pillows that look all ready for the next occupant. Nobody lives in them. They are just for show.

Visitors never see the third-floor hallways of double-locked rooms with their pairs of bunk-beds, nor are they shown the softening cells with jute-padded walls and a ring-bolt screwed into a floor corner opposite the shit bucket.

And of course, nobody ever tours the outbuildings. I only know myself because I was part of the work crew replacing shingles, and even so I was not allowed inside. But I saw through the windows a row of wooden-slatted cells with bare wood floors like a horse barn, except the stalls had brass padlocks holding them closed.

Cowering in the corners were children so wretched or violent as to be animals themselves, shit-smeared and reeking in filthy rags, matted hair and rotten mouths. It makes me shudder to think of them, all the more because I couldn't tell if they were born that way or made.

Mr. Mugridge likes to show us off. He considers interactions with the community to be sacred occasions that require formal dress, himself togged out in swallowtails with the high collar fashionable fifty years ago. The attendants don starched gray coverups with high peaked hats, vaguely military.

We have a few of these displays throughout the year, but none as important as the Apple Carnival. It is an annual town frenzy of self-congratulation and hypocrisy when the gentler and more biddable feebs and moral defectives are be scrubbed, dressed, and exhibited as a sop to communal charity.

This year is to be a memorial to little Eddie Follet, a nine-year-old scion of a Glenwood dentist. Young Eddie fell into a grain bin and smothered himself dead last April. "I'd have pushed him if I'd been there," says Cholly, reading the Opinion-Tribune over my shoulder. "Little snot."

"You knew him?" I ask.

"I know most people in this town. There's at least a dozen Follets in that branch, and probably more that can't lay honest claim to the name. Doc Follet has wandering hands once he gets gas into a girl. Look here." He taps an article in the corner. "Ben Overman, aged about twenty-one years, committed suicide about three miles outside of town, apparently by shooting himself in the head with a revolver." He snorts.

"What's funny about that?" I say, thinking of my own father.

"About twenty-one, about three miles, apparently by shooting himself. This writer don't want to make any solid declaration of fact. Everything is an estimation. Why do you suppose?"

"Maybe he doesn't want to get into trouble by getting it wrong."

"Then he is in the wrong profession. He ought to take up the law."

Great details!