Touchstone

Short Historical Fiction

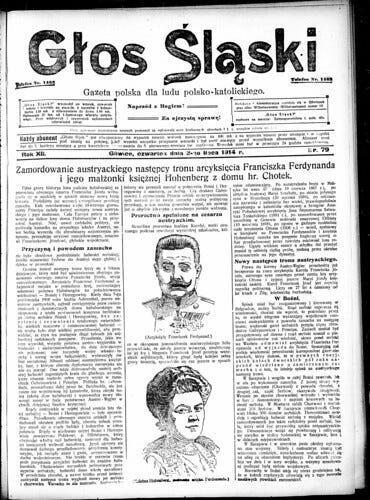

This is a story I submitted to the NYC Midnight historical fiction contest last year. I found it interesting to explore a lesser-known villain and discover the story behind his action. In this case it’s Gavrilo Princip, the young nationalist revolutionary whose action (it can be argued) set the twentieth century on a path to endless war.

Gavro squints in the morning sun as he joins the crowd lining both sides of the Appel Quay, Sarajevo’s proudest boulevard. The throng surges with excitement at the approaching motorcade, the people waving flags, blowing horns, and generally making fools of themselves. To his left a small girl eats roasted almonds out of a paper cone bought from one of the numerous street carts taking advantage of the royal visit.

Gavro can smell the smoky nuts and feels his empty stomach churn. She fumbles and drops the cone, crying out in dismay as the almonds scatter in the mud. Her father hands her a miniature flag of Austria-Hungary, the saffron coat of arms quaintly matching her yellow hat. Mollified, she waves it.

Everyone in Sunday best––white linen suits and straw hats on the men, bloom-colored dresses and broad bonnets on the women, umbrellas and walking sticks and polished white shoes. Gavro feels conspicuous in his filthy forest boots and mud-smeared woolen overcoat as he steps out to look up the street. He feels the flat cold shape of the grenade in his left pocket, the hard cold shape of the Browning automatic in the right.

Someone cries There they are!

Gavro sees the sun winking on the polished brass radiator of the motor coach that carries the Archduke and the general and God knows what other parasites. Gavro’s heart quickens with a surge of fresh hatred. Swine. We’ll serve you out.

A band strikes up Gott Erhalte, Gott Beschütze, the national anthem of Austria-Hungary. The crowd presses in, Gavro standing out front like the figurehead of a ship. The approaching coach overflows with passengers festooned in lace and plumed helmets that dance in the breeze.

Now they are almost to the bridge where Nedeljiko positioned himself as the first of the seven assassins. Gavro is the last, a punishment for questioning Nedeljiko’s authority. He tightens his mouth in a now-habitual gesture of repressed resentment.

As though thinking his name has summoned him, Nedeljiko steps out of the crowd and lobs his grenade at the passing coach, a small orb arcing high.

It does not land among the passengers but bounces off the folded-down bonnet and onto the street where it explodes beneath the second automobile in a gout of orange flame. A woman screams as the Archduke’s car lurches to a stop.

Gavro watches Nedeljiko leap over the bridge-rail and into the river, landing on his hands and knees in the inches-deep water. Quick after him are the gendarmerie in blue shako hats and silver swords that clatter against their high boots, their modern automatics in their hands.

Nedeljiko starts to run, but seeing more police crowding the far bank, plunges his hand into his pocket for the phial of cyanide. He is shouting something to the crowd, probably some trope about striking a blow for the Yugoslav state. With dramatic flair he upends the poison into his open mouth, staggers a few feet and vomits a white foam into the swirling water. The police encircle him and drag him up the bank.

Gavro looks back up the boulevard. The crowd is becoming riotous, surrounding the burning second car and pulling out the injured passengers. The Archduke’s motor coach is still stopped, so Gavro moves toward it. Just then, the driver puts the car into gear and, heedless of the pedestrians, accelerates across the bridge, people leaping to get out of the way.

“Did you see?” asks Ciganović, who has crept up behind him. “We have failed!”

“You were next in line,” says Gavro. “Why did you not step forth and kill the Archduke?”

“There was no time,” says Ciganović. He looks away. “The people in the second car. A woman had her leg blown off.”

Gavro notices Ciganović is weeping. He wants to hit him, but instead walks away.

Ciganović is right about one thing. They have failed.

Still, all may not be lost. He has not come so far only to give up now. He checks to see that no police are approaching, then walks briskly toward Franz Josef street in the heart of town. Perhaps there will be another chance.

Nobody gives him a second glance. He is an unassuming figure, scrawny in the too-large overcoat, pale and drawn.

“You will never amount to anything,” Gavro’s father told him when the boy announced his intention to join the military. “So why even try?”

Petar Princip had served in the Bosnian army and spoke with the authority of experience. He’d returned from the war against Austro-Hungary a shell of his former self, bitter and brooding.

But Gavro ignored him, walking the two hundred versts to Sarajevo where the military rejected him out of hand for being undersized and, they thought, sickly. Determined to make something of himself, he enrolled in Gymnasium, the school for merchants.

He loved it from the first, his quick mind eagerly consuming everything placed before it. Bosnian history was the greatest enchantment. Gavro felt a growing kinship with the Slavs. Like himself, they had been subjected to injustice and tyranny. In his second term he wrote an essay that condemned Austro-Hungarian imperialism in scathing language. His teacher, a Yugoslav nationalist, gave him highest marks, but the next day Gavro was summoned to the headmaster’s office.

“Gavrilo, this is extraordinary work,” he said, hands folded on his desk like a condemning judge. “But you must abandon your hatred. It will destroy you.”

One day a young man presented him with an embossed envelope. The card said Nedeljiko Čabrinović invited him to the Sanctum at four o’clock tomorrow. Gavro was mystified. Nedeljiko Čabrinović was the most popular student at the school, an accomplished athlete, even an aristocrat. What could he possibly want with Gavro, a peasant from the sticks who had no money, no important friends, and was a weakling besides?

The Sanctum was a set of rooms on the top floor of the Union reserved for upperclassmen. Nedeljiko was sitting at a small round table when Gavro arrived promptly at four, sweating and puffing from the six flights of stairs.

“Please,” said Nedeljiko, pointing to a chair. “Sit. Tea?”

A young man appeared with a silver samovar which he set between them, then retreated back into the shadows. Nedeljiko filled both their cups and sat back.

“One of my friends in the administration brought you to my attention,” he said, sipping. “You’ve been here, what, two terms?”

“Yes,” said Gavro.

“My friend says that you have highest marks of anyone in the school. And he showed me this.” He picked up Gavro’s essay. “It’s quite good. You seem to hate the Austrians?”

“With all my heart.”

“Why?”

“They killed my father,” he lied.

“Where are you from?”

“Olbjaj.”

“Never heard of it.”

“It is a small village in the west.”

“Was your father a landowner?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Your father. Did he own land?”

“He was a serf,” he said, adding “but he died fighting for Bosnian independence.”

As he said this, he realized how much he wished it were true.

Nedeljiko nodded. “We can use you.” He rummaged in his valise and removed a small stack of books. “I need you to read these and write a report on each by Friday.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It is my homework. I am too busy to be concerned with plebeian matters.”

So Gavro joined Young Bosnia and developed a passion for a single Slavic nation freed from the dual oppressions of the Ottoman and Austrian Empires. “We are caught between the hammer and anvil!” cried Nedeljiko, the group’s de facto leader. “We demand equality for all Slavs!”

But within the group there was no equality whatsoever. Nedeljiko was a worse tyrant than Gavro’s father had ever been, treating him more like a slave than a comrade. In addition to making him do all his schoolwork, Nedeljiko made him launder his shirts, bring him tea, and write all the speeches that Nedeljiko pompously gave on every occasion. Punishment was swift and severe, Nedeljiko brandishing his physical superiority by savagely beating Gavro for the slightest infraction.

But the worse it got, the easier it was to bear. As his hatred grew, he became stronger in this personal martyrdom to the Yugoslav cause. For Gavro, all Slavs were brothers regardless of birthplace, social status, or even religion. To this end, he made it a point to recruit as many Muslim Serbs as he could.

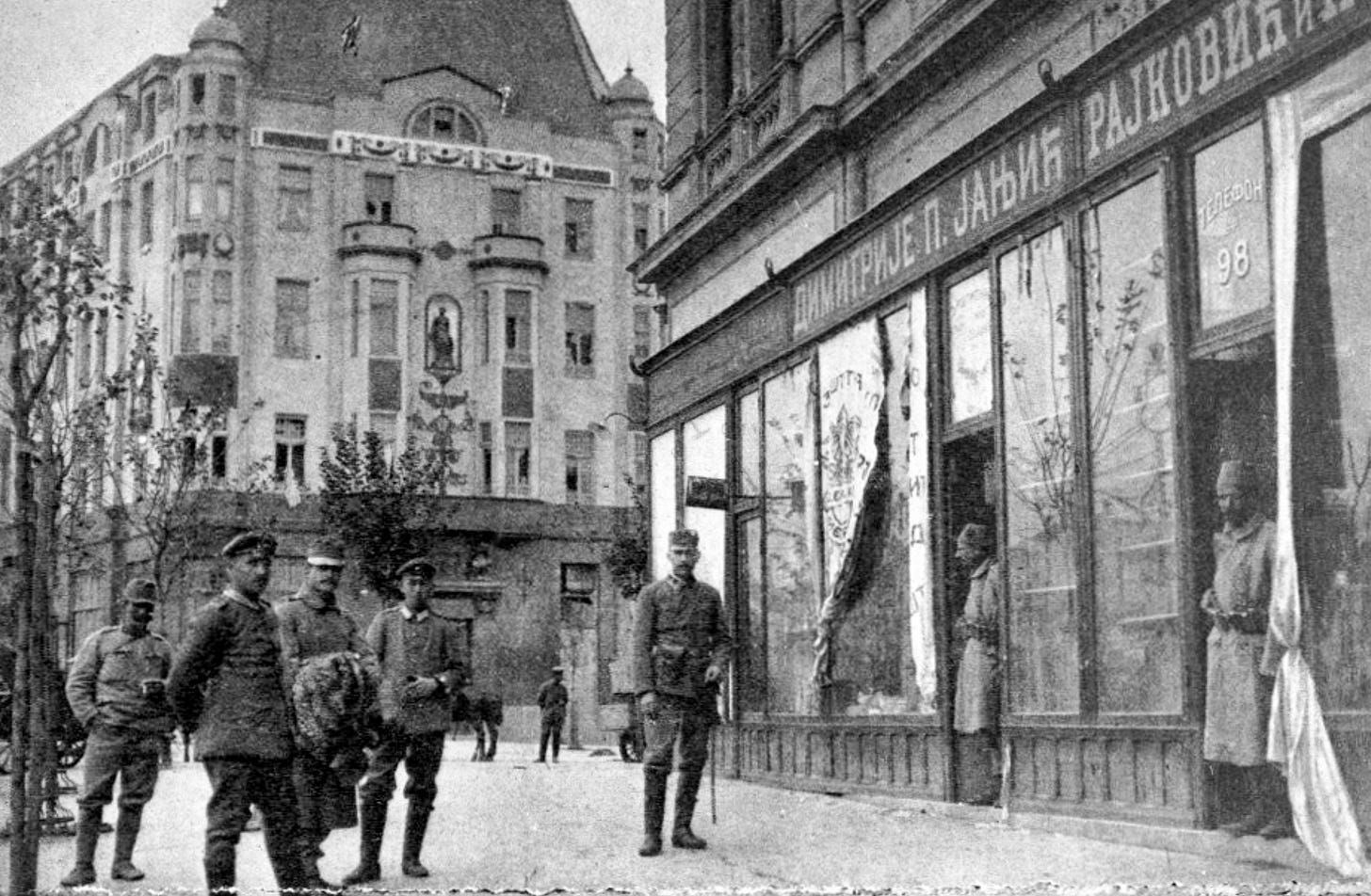

This proved to be his undoing. At an indoor rally, a large group of devout Muslim students got up to leave for prayer. Nedeljiko, misunderstanding their intentions, ordered Gavro to stop them. A brawl broke out so severe that the police were summoned. An investigation was performed and most of the Young Bosnia members were expelled from the school, Nedeljiko and Gavro first among them. When a raid on the group’s headquarters resulted in the arrest of several members, Nedeljiko and Gavro fled to Belgrade.

Belgrade had difficulties of its own. An ancient, prosperous city, nobody there had witnessed much in the way of Austro-Hungarian oppression and most of the people enjoyed being subjects of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Nedeljiko found their indifference infuriating. “How can I wake them up?” he ranted.

“We need another Žerajić,” said Gavro.

Bogdan Žerajić was a member of Young Bosnia who in 1910 had emptied his pistol into the passing coach of the Austro-Hungarian governor of Bosnia. All five of Žerajic’s shots had missed, but he saved the sixth for himself and successfully blew his own head off, thus becoming the first great martyr of the Yugoslav cause.

“We should gladly follow in his footsteps,” Nedeljiko proclaimed. “Except I will not miss!”

One spring morning, Gavro was in a café reading a newspaper and saw that the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand would be visiting Sarajevo in late June as part of his tour inspecting the Imperial Army. Without a word, Gavro ran back to his room and wrote a detailed plan. A group of assassins would be stationed along the route, each armed with a pistol and grenade to strike a blow for Yugoslav independence. And as Nedeljiko boasted, this time they would not miss.

Gavro stands now among the milling crowd outside the Moritz Schiller Cafe.

As the morning wears on he becomes more and more dejected, certain that he and his co-conspirators will all be arrested by day’s end.

He hates that he’s a hundred meters from the Archduke, yet unable to move because of the mob of people gathered to hear the monarch’s speech.

With failing heart, he sees the crimson plumes of the Archduke’s shako bobbing over the heads of the onlookers.

He hears the car’s motor cough to life as the crowd eases back to allow it to depart.

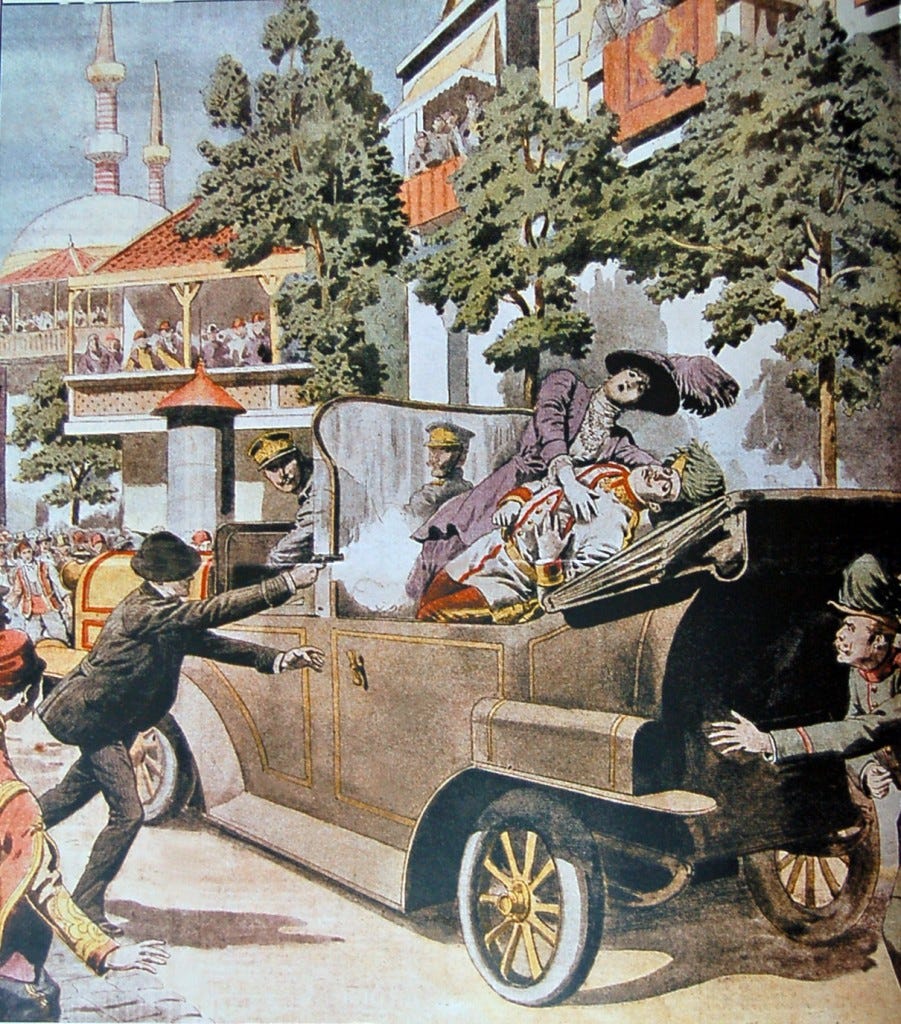

And then it’s there, a shining green limousine with tall wheels heading the wrong way up the street, the Archduke in the back, the general in the front seat flailing the driver, ordering him to turn around.

The car stops six feet from where Gavro is standing.

Gavro steps forward, whipping his pistol out.

The shocked Archduke turns his head.

He resembles a bird, his bright blue coat and upturned mustaches and ridiculous plumage.

The first shot pierces the Archduke’s gold-encrusted collar, hurling him backward.

Gavro aims at the general in the front seat, but the Archduke’s wife throws herself across her husband the instant he fires.

He’s shot her in the stomach.

Gavro’s pistol is torn from his hand and the blows rain down, knocking him into black unconsciousness.

Four years later Gavro lies in his prison cell of dying of tuberculosis.

The guards delight in informing him how many thousands were killed that day in this great war he started with his lucky shot.

But Gavro’s greatest remorse is not the war.

It is the very human grief on the Archduke’s face when Gavro’s bullet struck his wife.

The very moment Gavro realized he no longer hated him, or anyone.

I enjoyed this , especially the killer last line.